By: Brandon M. Macsata, CEO, ADAP Advocacy

ADAP Advocacy hosted its Health Fireside Chat retreat in New Haven, Connecticut among key stakeholder groups to discuss pertinent public health issues facing patients in the United States. The Health Fireside Chat convened Thursday, September 5th through Saturday, September 7th. An analysis of the negative impact pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) are having on the nation's drug supply chain, how state prescription drug "affordability" boards (PDABs) are threatening to undermine the 'Ending the HIV Epidemic' initiative, and the explosive growth in executive compensation among Covered Entities participating in the 340B Drug Pricing Program were each evaluated and discussed by the 31 diverse stakeholders.

|

| Photo Source: Getty Images |

The Health Fireside Chat kicked-off with a stakeholders reception. The retreat also featured three moderated white-board style discussion sessions on the following issues:

- Ripple Effect: How PBMs and Counterfeit Drugs Threaten Patients — moderated by Shabbir Imber Safdar, Executive Director at Partnership for Safe Medicines (PSM)

- Prescription Drug Affordability Boards: A Threat to Ending the HIV Epidemic — moderated Jen Laws, President & CEO at Community Access National Network (CANN)

- 340B Greed: Rising Revenues, Rising Executive Compensation, Rising Medical Debt...but Lower Charity Care — moderated by Brandon M. Macsata, CEO at ADAP Advocacy & Marcus J. Hopkins, Executive Director, Appalachian Learning Initiative (APPLI)

The discussion sessions were designed to capture key observations, suggestions, and thoughts about how best to address the challenges being discussed at the Health Fireside Chat. The following represents the attendees:

- Tez Anderson, Executive Director, Let's Kick ASS (AIDS Survivor Syndrome)

- Guy Anthony, President & Founder, Black, Gifted & Whole Foundation

- Ninya Bostic, National Policy and Advocacy Director, IDV, Johnson & Johnson

- Erin Bradshaw, EVP, Advancement of Patient Services & Navigation, Patient Advocate Fndn.

- Caleb Brown, Patient Advocate, and Research Associate, Yale University

- De’Shea Coney, Vaccine Access and Equity Coordinator, Iowa Department of Health

- Brady Etzkorn-Morris, Patient Advocate

- Earl Fowlkes, President & CEO, Center for Black Equity — unable to attend

- Vanessa Gannon, Head, Issue Advocacy, Genentech — unable to attend

- Alexander Garbera, Member, New Haven Mayor’s Task Force on AIDS, City of New Haven, CT

- Dusty Garner, Patient Advocate

- Kelsey Haddow, Patient Engagement, Rare Access Action Project (RAAP)

- Marcus J. Hopkins, Founder & Executive Director, Appalachian Learning Initiative

- Lisa Johnson-Lett, Peer Support Specialist, AIDS Alabama

- Ben Kelly, Senior Vice President of Pharmacy Management, Maxor National Pharmacy Services — unable to attend

- Jax Kelly, President, Let's Kick ASS (AIDS Survivor Syndrome) Palm Springs

- Karen King, Harm Reduction Specialist

- Kamaria Laffrey, Co-Executive Director, The SERO Project

- Jen Laws, President & CEO, Community Access National Network

- Kevin Lish, Patient Advocate, and Finance Director, SERO Project

- Brandon M. Macsata, CEO, ADAP Advocacy

- Judith Montenegro, Program Director, Latino Commission on AIDS

- Steve Novis, Director, Community Alliances & Government Relations, ViiV Healthcare

- Warren O'Meara-Dates, Founder & CEO, The 6:52 Project Foundation — unable to attend

- David Pable, Patient Advocate

- Kalvin Pugh, Patient Advocate

- Shabbir Imber Safdar, Executive Director, Partnership for Safe Medicines

- Dmitri Siegel, Alliance Development Director, Bristol-Myers Squibb

- Ranier Simons, Policy Consultant, Community Access National Network

- Jonathan Sosa, Patient Advocate

- Robert Suttle, Patient Advocate

- Nicole Tomassetti, Government Affairs Associate, Capitol Strategies Group

- Jeremy Toney, Patient Advocate, and Research Coordinator, Henry Ford Health

- Denise Tucker, Executive Director, State Policy, Merck

- Olivier Viel, Associate Director, Policy & Government Affairs, Merck

ADAP Advocacy is pleased to share the following brief recap of the Health Fireside Chat.

Pharmacy Benefit Managers:

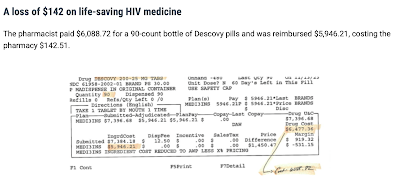

- To understand the PBM problem, read: "Are below cost reimbursement practices by Pharmacy Benefit Managers creating opportunity for criminals to enter the legitimate supply chain?" (PSM article, handout, and video)

- To understand why pharmacists are looking for bargains, read the story of pharmacist Jackie Weaver in: "Drugmaker Gilead Alleges Counterfeiting Ring Sold Its HIV Drugs" (WSJ)

- To understand how criminals operate in this space, watch: "Fraud in a bottle: How Big Pharma takes on criminals who make millions off counterfeit drugs" (CNBC)

- To see a recent example of this ongoing problem, read: "Gilead Sciences alleges dangerous drug-counterfeiting operation at two NYC pharmacies in lawsuit"

PDABs:

The discussion, Prescription Drug Affordability Boards: A Threat to Ending the HIV Epidemic, was led by the Community Access National Network's (CANN) President & CEO Jen Laws. CANN focuses on public policy issues relating to HIV/AIDS and viral hepatitis. Previously characterizing PDABs as "price control wolves in sheep's clothing", Jen once again stressed the potential dangers behind these entities making potentially life and death decisions without having all of the facts and real-world implications of how those decisions could adversely impact patient care. Aside from cancer drugs, antiretroviral therapies for HIV are disproportionally being targeted by PDABs in numerous states. The mechanism being eyed by these boards to "control" drug costs is what is known as the Upper Payment Limit (UPL), which is the maximum reimbursement rate above which purchasers throughout the state may not pay for prescription drug products.

-updated-07-01-24.jpg) |

| Photo Source: CANN |

Earlier this year, CANN untangled the warnings and concerns regarding PDABs. On the surface, they are presented as a simple solution to a complex issue. As further background, Jen pointed to an analysis done by CANN's State Policy Consultant, Ranier Simons, in which he summarized: "The complex problem is the extremely high healthcare expenditure in the United States. Accessing modern healthcare results in high amounts of spending from costs associated with hospitals and other facilities, medical technology creation and utilization, and even prescription drugs. Although prescription drug expenditures are only a small part of the billions spent annually on healthcare, the price of prescriptions is the low-hanging fruit that PDABs aim to attack. The money patients pay for prescription drugs is assuredly a financial burden for many. However, while PDABs aim to expressly lower the direct cost of prescription drugs for patients, their trajectory does not achieve that goal. Their actions have the potential to cause access issues in addition to potentially increasing out-of-pocket costs to consumers. This is especially true since the primary means PDABs lean toward to lower costs is the upper payment limit. Moreover, while CANN has a focus on PDAB potential outcomes regarding HIV drugs, all drugs are of concern, given that people living with HIV (PLWH) have multiple co-morbidities. Any threat to any drug utilized by vulnerable chronic disease communities is a threat to all."

Jen walked attendees through how 340B rebates, often the lifeline for smaller, community-based providers, could be drastically reduced as a result of the "affordability determinations" being made by PDABs. He noted how CANN has routinely pushed back against the fast-paced approach in some states to rush into making affordability determinations, including submitting testimony to the PDABs in both Colorado and Maryland. Jen outlined why UPL adjustments won’t address patient access or affordability, nor will is save patients a dime. He demonstrated his point with a fictitious provider and the 340B rebates it would receive under current law, as compared to the amount after UPL adjustments. Most providers would be forced to cut services, layoff staff, and potentially cease operations.

The following materials were shared with retreat attendees:

- NASHP Model State Legislation

- CANN PDABs Action Center

- Health Plans Predict: Implementing Upper Payment Limits May Alter Formularies And Benefit Design But Won’t Reduce Patient Costs

- NMQF Webinar: State Prescription Drug Affordability Boards & Health Equity

- NMQF: 340B As a Health Equity Tool

- Ripple Effect: How PBMs and Counterfeit Drugs Threaten Patients

- Prescription drug affordability boards do more harm than good

ADAP Advocacy would like to publicly acknowledge and thank Jen for facilitating this important discussion.

340B:

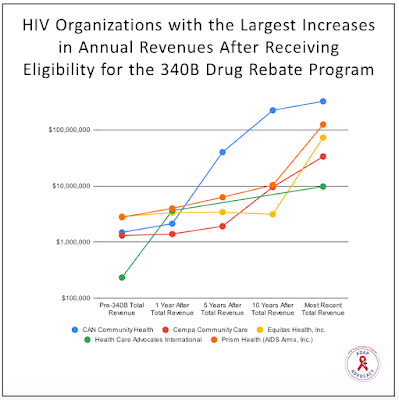

Marcus J. Hopkins, Founder & Executive Director, Appalachian Learning Initiative, concluded the retreat with a discussion focused on the 340B Drug Pricing Program and its potential impacts on the annual revenues and executive compensation amounts at Covered Entities that are eligible to receive rebates from the program, as well as the provision of charity care at cost by hospital entities who qualify. There has been an exponential increase in the number of Covered Entities from 1992 to 2021, increasing from just ~1,000 entities in 1992 to over 50,000 in 2021 (increasing from 12,700 in 2020 as a result of relaxed standards and enforcement due to the COVID-19 pandemic), which Jen Laws, President & CEO of the Community Access National Network, explained, along with additional insights from other attendees with professional knowledge of the program, that the first major increase that occurred in 2010 happened because the Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA)—the federal agency in charge of administering the program—lifted the cap on the number of contract pharmacies with which covered entities could provide medications. This decision essentially allowed organizations that did not have an on-site pharmacy to contract with external pharmacies to provide their services either at another in-person location or via mail delivery, which was becoming a more popular way to provide medications in the late-2000s and early-2010s.

The discussion brought attention to many of the barriers encountered when attempting to access information about 340B revenues from Covered Entities other than those that qualified as an AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) entity, including (but not limited to):

- The total lack of transparency required by HRSA for non-ADAP covered entities to disclose the amount of revenues received from the program or how those revenues are utilized;

- The numerous methods through which hospitals are able to legally create multiple other legal entities to shift funds, profits, and losses away from the primary hospital, and;

- The ability of hospitals to purchase other hospitals and private practices and counting those purchases as both revenues increases and losses on separate line items in the federal and state tax filings.

This brought up the issue of vertical integration—the practice of a company purchasing and controlling different stages within a chain of goods or services. For example, large hospital systems across the United States have spent much of the last two decades purchasing regional hospitals, local private practices, and private pharmacies, essentially making themselves the largest single employers in many states. This benefits the hospital system by increasing their revenues through ensuring that they are essentially the only providers of healthcare services and medications in a region. This allows them to absorb the 340B revenues from many of these entities, as each entity they purchase (known as "child sites") then fall under their 340B eligibility. Major hospital systems, such as Bon Secours Mercy Health based in Virginia, have been accused of using 340B revenues (which are supposed to be utilized to increase the availability and affordability of care for lower-income patients) to open new locations in more affluent areas in order to decrease the amount of uncompensated care and increase the amount of paid services, further driving up annual revenues.

Questions centered around how ADAP Advocacy (and CANN) can better elucidate abuses in the 340B program by hospital entities and mega service providers, but also highlighting good faith actors—Covered Entities who are using the program as it was intended to be used—in order to better compare and contrast the difference between Covered Entities.

The following materials were shared with retreat attendees:

- The 340B Drug Pricing Program and its Potential Impacts on Annual Revenues, Executive Compensation, and Charity Care Provision in Eligible Covered Entities

- For 340B hospitals, financial strength does not translate into charity care

- Reforming 340B to serve the interests of patients, not institutions

- What Should a Compliance Officer Do About 340B These Days? Journal of Health Care Compliance

- Public hospitals may use the 340B program differently than nonprofit hospitals

- Access to the 340B Drug Pricing Program: is there evidence of strategic hospital behavior?

- US hospital service availability and new 340B program participation

ADAP Advocacy would like to publicly acknowledge and thank Marcus for facilitating this important discussion.

Additional Fireside Chats are planned for 2024 in New York City (December).