By: Ranier Simons, ADAP Blog Guest Contributor

Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) don’t make medicine or dispense medicine, but their business decisions determine what medicines you have access to. Some of those decisions are now creating openings for drug counterfeiters to enter the legitimate supply chain, according to a report by the Partnership for Safe Medicines (PSM) and subsequent analysis by the Community Access National Network (CANN). This is a pressing matter because counterfeit drugs can result in adverse side effects, treatment failure, resistance, toxicity, and death.[1]

|

| Photo Source: Center for Medical Economics & Innovation |

The U.S. market value for PBMs in 2023 was $523.9 billion.[2] PBMs have always been marketed to reduce drug expenditures for payers and lower drug costs for patients, but historically, that has not happened. The $523 billion results from questionable practices that bring in sizable profits for PBMs while shortchanging insurance payers with opaque contracts and to the detriment of patients. Some patient advocacy groups have argued PBMs are harmful to patients’ health. One common PBM practice, below-cost pharmacy reimbursement, creates supply chain contamination opportunities.

Insurance companies reimburse pharmacies for the medications they dispense to patients. A pharmacy purchases medication from a wholesaler and then submits a claim to a patient’s insurance to be paid for the medication. PBMs handle the payments to the pharmacies on behalf of insurance companies. In 2023, 332 million people in the U.S. had health insurance, and 275 million of them were served by Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) via commercial insurance, Medicare Part D, Managed Medicaid, and Medicaid Fee-For-Service.[3] Thus, pharmacies are forced to deal with PBMs. In order to dispense medications to patients with insurance, pharmacies must sign contracts with PBMs that are agreements to accept whatever price the PBM dictates for reimbursement. Currently, three PBMs control 75% of the health insurance market; thus, there is no competition.[4]

The predicament is that PBMs are reimbursing pharmacies below cost. This means that PBMs are paying pharmacies less money than the pharmacies spent to acquire the drugs. Effectively, pharmacies are dispensing drugs at a loss to serve patients. A real-world example of one of the big three PBMs' contracts with a pharmacy for brand-name drugs listed reimbursement of the average wholesale price (AWP) minus 25.5% + $0.00. The same contract listed AWP minus 57% + $0.00 for generics.

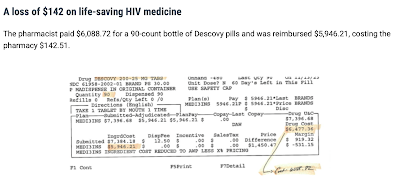

The following examples are actual claims submitted by pharmacies and their resulting losses based on the PBM contracts. For Biktarvy, a pharmacy acquired a 30-day wholesale supply of the drug for $3700.36, but the PBM only reimbursed $3661.75, resulting in a loss of $38.61. For Genvoya, a pharmacy paid $3,534.78 and was only reimbursed $2,852.92, resulting in a loss of $681.86. A pharmacy in Florida purchased a 30-day supply of roflumilast for $43.86 and was reimbursed by a PBM for $11.22, resulting in a $32.64 loss. PSM has many other examples of losses on other various pharmaceuticals here.

|

| Photo Source: Partnership for Safe Medicines |

The situation is dire, as indicated by a statement given by a pharmacist from an independent pharmacy in Weatherford, Texas:

“I spent hours on the phone with my wholesaler and even the drug manufacturer trying to explain that we simply cannot sustain such drastic underpayment on this critical medication and every time my concerns fell on deaf ears. After years of trying to affect some kind of change on either the cost or the reimbursement, we simply could not take losses of any kind on a drug that has a price tag of $3000.00. Our losses ranged from $17.46 to $572.30, and we were expected to accept this arrangement from day one. We were a safe haven and trusted health partner for these patients; however, we were forced to notify our patients that we would no longer be able to provide this life-saving medication.”

This pharmacist decided to stop providing the referenced medication. However, all pharmacists do not make that decision, which creates opportunities for criminal exploitation.

Pharmacists want to do what they can to provide the medicines people need. When they cannot source medications through their prime wholesalers, they turn to the secondary wholesaler market. Secondary wholesalers are also licensed by the state, and many are secure and reputable channels, but this is also where criminals operate. Criminal counterfeiters take advantage of the situation and set up marketplaces for popular, expensive drugs, using black-market diverted or counterfeit products at prices lower than traditional wholesale sources.

Pharmacies do not haphazardly search for and purchase lower-cost medications. They do their due diligence to make sure they are sourcing proper supplies. However, counterfeit criminals have sophisticated and elaborate systems to perpetrate fraud. They sell through companies with legitimate state-issued wholesale licenses and use forged Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA) transaction tracing histories. A deep dive into the paperwork can reveal the forgery. However, it takes significant resources of time and effort to dig into that kind of tracing. Resources that pharmacies do not have. Thus, when things have the appearance of propriety, pharmacists get duped by criminals, and patients get sold fraudulent medication.

|

| Photo Source: Partnership for Safe Medicines |

In 2022, the U.S. District Court unsealed documents of a civil case in which Gilead Sciences sued a group of criminals. The criminal enterprise distributed over $230 million of counterfeit drugs, some of which were HIV antiretroviral medications.[5] Some of the drugs were diverted, meaning they were purchased from people who had obtained them legitimately and resold on the black market. Some of the drugs were bottles containing medication that did not match what was on the label. Diverted medication indicates that patients were not adhering to their treatment regimens since they were selling their medications. The mislabeled medication bottles meant patients could have been ingesting medications not meant for them, in improper dosages, and possibly contaminated. Situations such as PBM below-cost reimbursement contribute to creating a demand for cheaper medications in an artificially created predatory pricing-induced supply scarcity.

Low PBM reimbursement not only endangers the drug supply chain but also puts independent pharmacies out of business. Pharmacies cannot operate under fiscal loss. In addition to low reimbursement rates, PBMs give pharmacies very low or often zero dispensing fees, which pharmacies need for operating costs. Moreover, PBMs saddle pharmacies with many other opaque fees, audits, and clawbacks, adding to their financial burden. When pharmacies go out of business, patients lose access. This is especially true in areas with very few pharmacies for a large geographical region. If a pharmacy closes, entire communities lose familiar and convenient continuity of care.

A group named Pharmacists United for Truth and Transparency wrote a letter to one of the big three PBMs. A quote from this letter explains what needs to be done: “Reimburse independent pharmacies the full drug acquisition cost and eliminate the practice of reimbursing above some and below other drug costs. Make a fair and universal reimbursement policy the unbreakable operating principle of the PBM-independent pharmacy partnership.” PBM reform is not just fiscally sound; for patients, it indeed could mean the difference between life and death.

[1] Williams, L., McKnight, E. (2014, June 19). The real impact of counterfeit medications. Retrieved from https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/counterfeit-meds#:~:text=The%20use%20of%20substandard%20drugs,enforced%20to%20prevent%20this%20crime

[2] Fortune Business Insights. (2024, April 19). Pharmacy benefit management market. Retrieved from https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/pharmacy-benefit-management-pbm-market-103496

[3] Mikulic, M. (2023, May 22). Number of Americans served by PBMs by insurance type 2023. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1172652/pbms-number-of-served-us-persons/

[4] The Partnership for Safe Medicines. (2023) Are below cost reimbursement practices by Pharmacy Benefit Managers creating opportunity for criminals to enter the legitimate supply chain?. Retrieved from https://www.safemedicines.org/2024/02/pbmblackmarket.html

[5] Gilead Sciences, Inc. et al v. Safe Chain Solutions, LLC et al. Retrieved from https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/legaldocs/dwpkrodwdvm/gileand-amended-2022-09-28.pdf?utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=newsletter&utm_campaign=daily-docket&utm_term=DailyDocket-MailingList%20v2

Disclaimer: Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of the ADAP Advocacy Association, but rather they provide a neutral platform whereby the author serves to promote open, honest discussion about public health-related issues and updates.