By: Marcus J. Hopkins, Founder & Executive Director, Appalachian Learning Initiative

Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010, millions of Americans have gained access to health insurance and other forms of healthcare coverage which they were previously unable to afford. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), a record 31 million Americans have access to healthcare coverage through the ACA’s Marketplace or Medicaid Expansion coverage (HHS, 2021). And yet, for a significant percentage of Americans, healthcare has not become, despite the name of the law, “affordable.”

When we talk about “affordability,” we often speak in terms of average numbers—the average costs of services and prescriptions; the average costs of insurance premiums and deductibles. By those measures, the ACA has failed:

- The cost of services has increased at an average annual rate of 3.5% per year over the past 20 years (Peter G. Peterson Foundation, 2022). Several factors contribute to this increase in costs, including the introduction of new and innovative technologies leading to more expensive procedures and products, the complexity of the U.S.’s overly complex multi-payor healthcare system that naturally leads to administrative waste, and the decrease of competition as hospital systems consolidate and take over smaller hospitals.

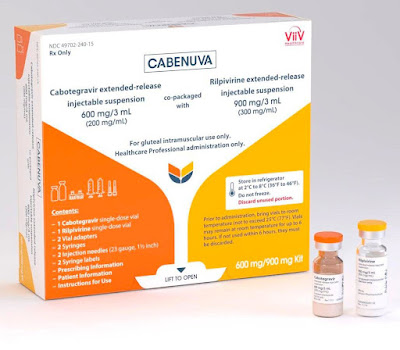

- The cost of prescription drugs has increased on an annual average of around 5% (Keown, 2022). Two HIV drugs, Biktarvy and Descovy (Gilead Sciences), saw price increases of 5.6% in 2021 which, according to a Gilead spokesperson, are offset by rebates and other discount programs (Keown).

- The cost of premiums has increased on an annual average of 11.6% (Antos & Capretta, 2020). Deductibles have risen dramatically, as well, increasing from an average of $2,425 in 2014 to $4,500 in 2020 for Silver Plans offered on Healthcare.gov (Antos & Capretta).

While these costs have increased at a consistent rate, the Real Median Personal Income in the U.S. has largely stagnated since the late-1990s, hovering between $30,000 and $37,000 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2022). This translates to the reality that, while the costs associated with healthcare services and treatments have increased, median incomes have not increased in conjunction to support those increased expenditures.

According to a recent report released by Peterson Center on Healthcare and the Kaiser Family Foundation, although 90% of Americans now have access to some form of health insurance coverage (private, employer-sponsored, or public), medical debt remains a persistent problem for 23 million people—nearly 1 in 10. This is especially true for Americans with lower incomes, Black Americans, and patients with significant medical needs. In terms of age, patients aged 35-64 were more likely than any other demographic to have significant medical debt. In terms of geographic location, people living in the South or in states that have not expanded Medicaid were more likely to have significant medical debt (Rae, et al, 2022).

Other aspects of the ACA—such as the 80/20 rule, requiring insurers to spend at least 80% of the premiums they collected on medical claims—were designed to limit the profits made by insurance companies. If insurers fail to meet that percentage, they are required to rebate the difference to policyholders. In the early years of the ACA, this resulted in billions in rebates to consumers. However, insurers have successfully devised numerous schemes to ensure that consumers pay more, and insurance provider profit margins stay high.

One such mechanism involves a practice referred to as “Co-Pay Accumulator Programs.”

What Are Co-Pay Accumulators and How Do They Work?

Co-Pay Accumulator Programs are stipulations included in many private and employer-sponsored health insurance plans, often hidden in the “fine print.” Under these programs, money paid to pharmacies and healthcare providers via coupons, assistance cards, discounts, product vouchers, and other third-party sources does not count towards patients’ deductibles or out-of-pocket maximums (OPMs). Since reaching a deductible or OPM makes the insurance company responsible for any further cost of treatment and services covered under a plan, delaying these benchmarks makes patients liable for more costs, increasing the amount they end up paying for prescriptions and other services.

Co-Pay Accumulator Programs save money for insurers by passing along higher costs to patients. For instance, a patient with hepatitis C might be prescribed a direct-acting antiviral (DAA) costing $28,000 per month. Even if an industry co-pay assistance program (CAP) only covers up to 25% of the drug’s cost, meaning $7,000, then just by paying for the first $3,500 dose, the CAP will already meet the patient’s $3,000 deductible. The patient only pays a token amount out of pocket, perhaps $5, while the CAP pays the other $3,495, and all future doses are billed to the insurer.

However, if the plan includes a co-pay accumulator program, that CAP payment will not count towards meeting the patient’s deductible. Instead, the patient uses the CAP for the second dose as well, hitting the CAP maximum of $7,000 yet even then still not meeting their plan’s deductible. With no more help from the CAP, the patient then has to spend $3,000 out of pocket for the next dose before finally hitting their deductible. This saves the insurance company $10,000 by costing the patient $3,000 and the CAP $7,000 before the insurance company even begins helping to pay for the drug. (Hopkins, 2021)

It is our belief that regardless of the source of payment—be it manufacturer coupon, AIDS Drug Assistance Program, or other patient assistance organization, such as the Patient Access Network (PAN) Foundation—all payments should count toward both deductibles and OPMs.

How Many Patients Are Impacted?

According to a 2018 analysis by Zitter Health Insights, 12% of patients with commercial plans were subject to Co-Pay Accumulator Programs in 2018, with 44% of commercial plans including Co-Pay Accumulator Programs. They predicted that 40% of patients would be impacted in 2019 with that number expected to grow annually (Schweitz, 2019). Many patients who are impacted, however, are unaware that their plans contain Co-Pay Accumulators Programs in no small part due to companies using seemingly innocuous language such as “Out-of-Pocket Protection Program” (Express Scripts), “True Accumulation” (Caremark), or “Coupon Adjustment: Benefit Plan Protection Program” (UnitedHealthcare) (Hopkins, 2021).

|

| Photo Source: The Matrix Consulting, LLC |

How Can We Address Co-Pay Accumulators?

At the end of 2021, only state-level action had been successfully undertaken to prohibit the inclusion of Co-Pay Accumulator Programs, with twelve states and Puerto Rico having passed such legislation:

- Arizona (HB 166)

- Arkansas (HB 569)

- Connecticut (SB 003)

- Georgia (HB 946)

- Illinois (HB 0465)

- Kentucky (SB 45)

- Louisiana (SB 94)

- North Carolina (SB 257)

- Oklahoma (HB 2678)

- Tennessee (HB 0619)

- Virginia (HB 2515)

- West Virginia (HB 2770)

In 2022, eleven states have introduced legislation to address Co-Pay Accumulators (that the author was able to find):

- District of Columbia (B24-0557)

- Florida (SB 1480) – FAILED; (HB 1063) – FAILED

- Iowa (H 2384)

- Maine (SP 621)

- Minnesota (SF 2136)

- Mississippi (HB 880) – FAILED; (SB 2470) – FAILED

- Missouri (SB 1031)

- New York (A1741); (SB 5299) – FAILED

- South Carolina (H 4987)

- Utah (SB 139) – FAILED

- Washington state (HB 1713) – FAILED; (SB 5610) – PASSED

In addition to state-level actions, Congress recently introduced the Help Ensure Lower Patient (HELP) Copays Act (H.R 5801). The HELP Copays Act, sponsored by Rep. A. Donald McEachin (D-VA-04), would ban co-pay accumulator programs by:

- Updating the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) definition of cost-sharing to require that all out-of-pocket payments made by or on behalf of a patient count toward the patient’s deductible and out-of-pocket limit. This would end co-pay accumulator programs in marketplace exchange insurance plans.

- Stipulating that any item or service covered by an employer health plan is part of the essential health benefits (EHB) package and therefore the plan must count any cost sharing toward patients’ annual limits. This would end the ACA’s EHB loophole that allows plans to deem certain categories of drugs as non-essential.

This addition to the ACA would require insurers to count co-pay assistance paid by any third party on behalf of the patient toward their insurance deductible or out-of-pocket maximum (Immune Deficiency Foundation, 2021). The bill has bipartisan support with 20 co-sponsors and 116 state and national organizations sent a sign-on letter via the All Copays Count Coalition to Secretary of Health and Human Services, Xavier Becerra, in support of the HELP Copays Act.

Whom Should We Contact?

While federal legislators continue to work on the HELP Copays Act, people can (and should) reach out to their state legislators to pass legislation at the state level to prohibit insurers from implementing Co-Pay Accumulators by any name. They may find their state legislators online.

At the federal level, the HELP Copays Act continues to sit in the House Committee on Energy and Commerce. People should reach out to their Congressional Representatives, which they may find here.

In addition to contacting members of the House, we urge patients to contact their Senators to ask for a companion bill to be introduced in the Senate. They may find their contact information here.

The ADAP Advocacy Association, Patient Access Network Foundation, and The Matrix Consulting, LLC, invite you to direct your elected representatives to the PAN Foundation’s excellent campaign:

End harmful co-pay accumulator programs online at https://www.panfoundation.org/end-copay-accumulators/.

References:

- Anton, J. R. & Capretta, J. C. (2020, April 10). The ACA: Trillions? Yes. A Revolution? No. Washington, DC: Health Affairs Blog: Health Affairs Forefront. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20200406.93812/full/

- Keown, A. (2022, January 04). Drug Price Increases for 460 Drugs in 2022. Urbandale, IA: BioSpace. https://www.biospace.com/article/a-new-year-means-price-increases-for-many-prescription-drugs/

- Peter G. Peterson Foundation. (2022, February 16). WHY ARE AMERICANS PAYING MORE FOR HEALTHCARE? New York, NY: Peter G. Peterson Foundation: Blog. https://www.pgpf.org/blog/2022/02/why-are-americans-paying-more-for-healthcare

- Hopkins, M. J. (2021, April 07). How “Co-Pay Accumulators” Stifle Healthcare Access and Empty Patients’ Wallets. Lost River, WV: Community Education Group: Rural Health Service Providers Network: Publications. https://secureservercdn.net/198.12.144.78/m60.322.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/CoPay_Accumulators-FINAL.pdf

- Immune Deficiency Foundation. (2021, December 02). Support the HELP Copays Act and fight unfair copay accumulators. Towson, MD: Immune Deficiency Foundation: News. https://primaryimmune.org/news/support-help-copays-act-and-fight-unfair-copay-accumulators

- Rae, M., Claxton, G., Amin, K., Wager, E., Ortaliza, J., & Cox, C. (2022, March 10). The burden of medical debt in the United States. Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/the-burden-of-medical-debt-in-the-united-states/?_hsmi=206419781&_hsenc=p2ANqtz--ts2CCK83uE9bi6lOcPJxnqqO0KQG5tOHocn9uAhHCAiYGFqKj4-5sQwvC4s15sMUuMqmLSQsg_QORW4rajQjwpITJZg&utm_campaign=KFF-2022-Health-Costs&utm_medium=email&utm_content=206419781&utm_source=hs_email

- Schweitz, M. C. (2019, January 22). The Cost-Shift Conundrum of Copay Accumulator Programs. Thorofare, NJ: Healio: News: Rheumatology: Practice Management. https://www.healio.com/news/rheumatology/20190114/the-costshift-conundrum-of-copay-accumulator-programs

- United States Census Bureau. (2022, March 11). Real Median Personal Income in the United States [MEPAINUSA672N]. Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MEPAINUSA672N

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, June 05). New HHS Data Show More Americans than Ever Have Health Coverage through the Affordable Care Act. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: About HHS: News. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2021/06/05/new-hhs-data-show-more-americans-than-ever-have-health-coverage-through-affordable-care-act.html

Disclaimer: Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of the ADAP Advocacy Association, but rather they provide a neutral platform whereby the author serves to promote open, honest discussion about public health-related issues and updates.