By: Ranier Simons, ADAP Blog Guest Contributor

The advent of new medicines has been fighting the scourge of the HIV/AIDS epidemic since the world became aware of it in 1981. Since, science has made many advances. Research birthed tests to detect the virus in the blood. Antiviral medications have evolved from AZT, and its serious adverse side effects, to the multi-drug daily one-pill regimens on the market today...and now injectable therapies. Despite all of the advances, there is still no cure. Medical science has made great strides in slowing down the virus and preventing infections in seronegative people. The disease has gone from being lethal to chronic. However, clearing it from the bodies of those currently infected is the goal scientists focus heavily on.

Medical science has turned to exploring genetic interventions when exploring ways to eradicate HIV from the body. Scientists have uncovered the various HIV genes and the viral proteins they produce.[1] This has facilitated the creation of drugs to block some of the virus’ activity inside the body. Now, science is focusing on how to genetically alter the human body to better fight against the virus.

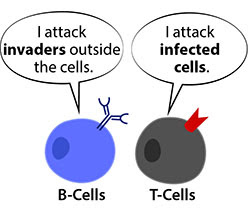

One such exploratory avenue is the genetic modification of the human immune system. Many people are familiar with the way HIV targets and damages the T-Cells, specifically the CD4 T-Cells. However, other parts of the human immune system are not as well known by the lay public, such as the B-Cells and the complement system. A new study out of Tel-Aviv involves the genetic modification of B-Cells using CRISPR and viral vectors. The future goal is a one-shot treatment for patients with HIV.[2]

|

| Photo Source: Commonwealth Fund |

The study examined engineering a person’s own B white blood cells to secrete high levels of anti-HIV antibodies in response to the virus.[2] Scientists have achieved some success in genetically engineering B-cells outside of the body. A few scientists have been able to use B-Cells engineered outside of the body to transplant into disease models with some success. However, the challenge is that using the approach for humans is very complicated. It requires very specialized medical centers, extensive blood compatibility testing of donor cells and recipients, and demanding protocols.[2]

The promise of the new study out of Tel Aviv is that B-Cells inside one’s own body could be genetically modified. This simplifies the process and guarantees the compatibility of the genetically modified cells. The study was led by Adi Barzel, Ph.D. senior lecturer, and Alessio Nehmad, a Ph.D. student from the school of neurobiology, biochemistry, and biophysics at the George S. Wise faculty of life sciences and the Dotan Center for Advanced Therapies in collaboration with the Sourasky Medical Center.[2]

The process uses viruses in combination with CRISPR technology. CRISPR stands for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats.[3] CRISPR technology was developed from how bacteria arm their immune system. The CRISPR technology can specifically identify specific stretches of a genome and cut it open. The Tel-Aviv study involves cutting open the DNA of B-cells and inserting genetic code that makes the cell generate neutralizing anti-HIV antibodies.

|

| Photo Source: Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News |

Two viral carriers are used to ‘infect’ the B-cells.[4] This is not a harmful infection. The viruses infect the B-Cells then the CRISPR technology cuts into the B-Cell genome and the proper loci (or genetic location). At that point, the genetic “snippet” that codes for the anti-HIV neutralizing antibody is inserted into the genome and closed. Going forward, the cells begin to secrete the new anti-HIV antibodies. Encountering HIV in the blood stimulates the B-Cells replicated and secrete even more neutralizing antibodies. The most crucial note is that when the HIV virus changes or mutates, the newly engineered B-Cells will also change accordingly to fight the new viral variant.

This study is essential as it could lead to a vaccine or one-time treatment. Additionally, the same technology could be developed to treat other infectious diseases or certain cancers caused by viruses, such as cervical cancer.

[1] Li, G., Piampongsant, S., Faria, N.R. et al. An integrated map of HIV genome-wide variation from a population perspective. Retrovirology 12, 18 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12977-015-0148-6

[2] FCould a One-Shot Treatment for Patients with HIV Be on the Horizon? (2022, June 14). Retrieved from https://www.genengnews.com/virology/hiv/could-a-one-shot-treatment-for-patients-with-hiv-be-on-the-horizon/

[3] Broad Institute. (2022). What is “CRISPR”? Retrieved from https://www.broadinstitute.org/what-broad/areas-focus/project-spotlight/questions-and-answers-about-crispr

[4] Tel-Aviv University. (2022, June 13). A new technology offers treatment for HIV infection through a single injection. Retrieved from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2022-06-technology-treatment-hiv-infection.html

Disclaimer: Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of the ADAP Advocacy Association, but rather they provide a neutral platform whereby the author serves to promote open, honest discussion about public health-related issues and updates.

No comments:

Post a Comment