By: Ranier Simons, ADAP Blog Guest Contributor

While overall HIV rates in the United States have been in decline, HIV is still a present and impactful issue. This is especially true for communities that experience a higher impact of HIV-related health disparities. One of these groups is the Latino community. The Latino community is second to the Black community about bearing the HIV burden. Several challenges converge in maintaining HIV’s disproportionate impact on the Latino community, including racism, stigma, language barriers, and access. In recently reported data for 2022 by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) the Latino community was about 18 percent of the U.S. population, but represented 33 percent of new HIV diagnoses.[1]

|

| Photo Source: Baton Rouge AIDS Society |

According to PlusInc, which addresses health disparities in the United States, HIV disproportionately impacts Black and Hispanic/Latino Americans (according to 2019 data). PlusInc’s HIV health disparities statement notes:

"While Black and Hispanic/Latino make up just 13.4% and 18.5% of the U.S. population, respectively, Black Americans account for 40.3% and Hispanic/Latino Americans account for 24.7% of the total population of Persons Living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). Additionally, this disparity extends to the incidence, with 42% of new HIV diagnoses occurring in Black Americans and 27.8% in Hispanic/Latino Americans. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 26% of new HIV diagnoses were among Black gay and bisexual Men who have Sex with Men (MSM), 23% were among Hispanic/Latino gay and bisexual MSM, and 45% among gay and bisexual MSM under the age of 35."

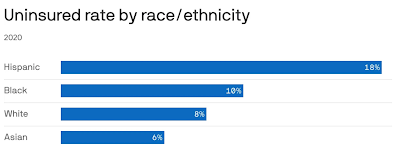

Access is a significant issue contributing to HIV challenges among Latinos. Latinos are the most underinsured/uninsured ethnic group in the United States.[2] Approximately 19 percent did not have health insurance in 2023, in contrast to 5.8 percent of White Americans and 8.6 percent of Black Americans.[3] Lack of health insurance means reduced access to HIV treatment and prevention, reduced or lack of primary healthcare services, or comorbidity management. Only 84 percent of the Latino community is aware of their HIV status, compared to 87 percent of the general population.[4] Of Latinos living with HIV who know their status, in 2021, only 72 percent received some kind of HIV care, 54 percent consistently remained in care, and only 64 percent were virally suppressed.[5]

Many Latinos are underinsured or uninsured due to financial barriers, language barriers, occupation, and even immigration status. In 2022, One-third of Latinos without health insurance were undocumented, and 37.7 percent were dependent upon Medicaid.[6] Some Latinos struggle to understand the healthcare system, and others do not seek out healthcare due to fear of deportation because of their immigration status. In states where they may be eligible for Medicaid, some Latinos in the process of acquiring citizenship are hesitant to apply out of fear of being deemed a public charge. However, only one-tenth of one percent of deportations result from public charge determinations.[6] Moreover, although ACA Medicaid expansion enables more adults to be covered, ten states have not expanded Medicaid, including Texas, Florida, and Georgia, which have large numbers of uninsured Latino residents.[6]

|

| Photo Source: Axios |

Two specific HIV care access challenges affecting the Latino community are PrEP and long-acting injectables. In 2021, Latinos represented 17 percent of PrEP users and 27 percent of new HIV diagnoses.[7] While PrEP could drastically improve outcomes, access barriers are high. Additionally, many Latinos living with HIV could greatly benefit from long-acting injectable treatments, such as Cabenuva, which would ameliorate adherence issues. However, it is expensive, and thus, paying for it out of pocket is impossible. Moreover, getting it covered in public assistance programs is also a challenge.

There are states, such as Texas, that do not carry Cabenuva on their drug formulary under the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP). Steven Vargas, Texas HIV advocate and long-term survivor, argues, “What I really want is for our Texas ADAP to be brought to its full potential in easing the burden of HIV on Texans.”

Vargas offers some novel ideas to help Latinos in need, as well as all Texans access Cabenuva. One way would be for Texas to expand Medicaid since Cabenuva is covered by Medicaid. Another option would be to utilize state ADAP funds to purchase insurance for those in need. Unfortunately, presently, in Texas, that is not possible due to exaggerated concerns about costs and solvency. A policy proposal Vargas suggested involves the federal agency, Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA). He suggests that the agency “...create a policy clarification mandating non-Medicaid expansion states to use ADAP funds to purchase health insurance for HIV-positive individuals. This would ensure more equitable access to healthcare and align with efforts to end the HIV epidemic in these intransigent states. Without such measures, the current inequities will persist, and achieving the goal of ending the HIV epidemic will remain out of reach.”

Stigma is another barrier from a policy, healthcare, and cultural perspective. Vargas points out, “Stigma is an overarching and deeply entrenched challenge significantly hindering Hispanic/Latino engagement in HIV services. Local efforts to increase community awareness and knowledge about HIV prevention and treatment are not prioritized and buried beneath the weight of stigmatizing edicts from our Governor and Texas Legislature.” A 2022 study shows that 11 percent of Latinos living with HIV reported encountering discrimination in a healthcare setting at least three times in a 12-month period.[5]

|

| Photo Source: The Hill |

Cultural stigmas and norms are also high barriers to improved HIV outcomes as well. Latino men who have sex with men accounted for the highest number of new HIV diagnoses in 2022. There is a sizeable Catholic influence in Latino culture. Thus, discussing sex and sexual health is not a widely socially acceptable norm, especially if one is gay. There is also the existence of marianismo and machismo. Marianismo is the idea that women should be subservient to men even in sexual encounters, including not wearing a condom if that is what the man desires. Machismo is the ideal that men should be masculine, dominant, and virile.[8] Social pressures and stigma cause many to be fearful of seeking out care and live secretly with their status if, they are positive. This could result in increased transmission by allowing social norms to influence decision-making when it comes to sexual health and partner selection.

Reducing the impact of HIV in the Latino community will require interventions from both policy and community perspectives. The Latino community is not monolithic. Thus, there is a need for stigma intervention that explicitly targets different groups, such as youth groups, church groups, and parent groups. One such national campaign is Celebro Mi Salud (I Celebrate My Health).[9] It is designed to normalize HIV and encourage people living with HIV to seek out care and stay in care. Policy interventions would include means to strengthen collaboration between communities and local governments. There needs to be more culturally competent and bi-lingual healthcare providers as well as those involved with helping Latinos in need navigate the challenges of poverty, food insecurity, homelessness, and immigration.

There is no single simple solution. Addressing the impact of HIV requires making people whole. A holistic approach means helping Latinos in need navigate the challenges of poverty, food insecurity, homelessness, and immigration, as well as healthcare. Providing stability with the basic needs of life facilitates making personal health a priority instead of an afterthought.

[1] CDC. (2024, May). Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2018–2022. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2024;29(No. 1). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv-data/nhss/estimated-hiv-incidence-and-prevalence.html

[2] Guilamo-Ramos, V., Thimm-Kaiser, M., Benzekri, A., Chacón, G., López, O. R., Scaccabarrozzi, L., & Rios, E. (2020). The Invisible U.S. Hispanic/Latino HIV Crisis: Addressing Gaps in the National Response. American journal of public health, 110(1), 27–31. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305309

[3] Vankar, P. (2024, July 10). Percentage of people in the U.S. without health insurance by ethnicity 2010-2023. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/200970/percentage-of-americans-without-health-insurance-by-race-ethnicity/#:~:text=Percentage%20of%20people%20in%20the,insurance%20by%20ethnicity%202010%2D2023&text=In%202023%2C%20approximately%20nineteen%20percent,national%20average%20was%209.1%20percent.

[4] Helmer, J. (2024, June 2). HIV/AIDS in Hispanic and Latino Populations. Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/hiv-aids/hiv-aids-hispanic-latino-populations

[5] The Body. (2024, April 30). How HIV Impacts Latinos in the U.S. Retrieved from https://www.thebody.com/health/hiv-aids-latinx

[6] Smith, C. (2024, April 22). Hispanics make up nearly half the nation's uninsured. Retrieved from https://www.governing.com/health/hispanics-make-up-nearly-half-the-nations-uninsured

[7] AIDSVU. (2022, July 29). AIDSVu Releases New Data Showing Significant Inequities in PrEP Use Among Black and Hispanic Americans. Retrieved from https://aidsvu.org/news-updates/prep-use-race-ethnicity-launch-22/

[8] Nuñez, A., González, P., Talavera, G. A., Sanchez-Johnsen, L., Roesch, S. C., Davis, S. M., Arguelles, W., Womack, V. Y., Ostrovsky, N. W., Ojeda, L., Penedo, F. J., & Gallo, L. C. (2016). Machismo, Marianismo, and Negative Cognitive-Emotional Factors: Findings From the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Journal of Latina/o psychology, 4(4), 202–217. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000050

[9] HIV.GOV. 2022. Celebrao Mi Salud. Retrieved from https://www.hiv.gov/es/respuesta-federal/campanas/celebro-mi-salud

Disclaimer: Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of the ADAP Advocacy Association, but rather they provide a neutral platform whereby the author serves to promote open, honest discussion about public health-related issues and updates.

No comments:

Post a Comment